Creators become change makers

Big ideas are great – but what will you create?

We all know the feeling.

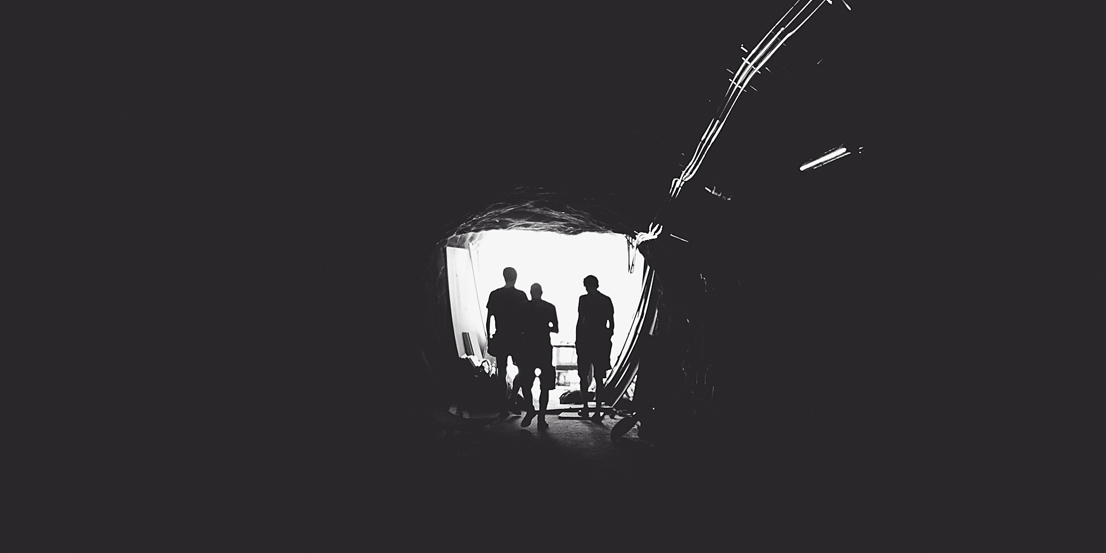

The feeling of satisfaction that comes from working on something. Something hands on. Something real. Nothing revolutionary – but something practical. Something anyone could have made, except this time, they didn’t. We made it.

If we’re lucky enough to have company, the satisfaction is somehow deepened. A shared moment of a job well done, a day well spent.

We might know the opposite too. The feeling of broaching burning out, with nothing but a stream of email conversations and calendar invites to show for it. The work is undeniable, but the end result is unfulfilling.

In an effort to break free from the chains of the office cubicle, many people turn to innovation for the answer. Thinking that if they can only dream up the next world changing idea, then life will finally be theirs for the taking. A big idea, a big success, a big payout … But then what?

Instead of devoting your life to a business that may or may not get you to the thing you really want to do, why not do the thing itself instead? Big ideas are great – but what will you create? It’s the making and doing that gets you closer to your path. Not one big idea, but small bursts of creativity, and small acts of disobedience.

Making and doing: The best way to get present

In an age of digital sickness, simple tasks like chopping onions become a gift.

The idea of grounding ourselves through making and doing will be familiar to anyone who has attended a yoga class. When we place our attention on the breath, on the feelings in the body, it is impossible to be swept away in the chatter of the mind. When we get moving, we get out of the head.

“Yogash Citta Vritti Nirodah,” one of the yoga sutras, is most often translated as “yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind.” Instead of analysing the movement or judging the thoughts, the mind becomes still and clear.

The Buddhist principle: “When chopping onions, just chop onions” is related to this, meaning, no matter how frustrating, boring, or even painful chopping onions may be, a Buddhist gives himself over to the work and it becomes simply a task: Nothing more, nothing less. This not only moves the mind away from the stories of this is bad, that is good, but brings a quiet joy to the moment. In an age of digital sickness, simple tasks like chopping onions become a buffer to mind chatter – or if we’re being generous – a gift.

The world wants makers and doers

Making and doing is not only the best way to get present or more creative; when you make something, you claim your place as a producer, and not just as a consumer. This is an important distinction in an age where, as an “average consumer,” we can sometimes feel at the mercy of the moguls, people who might not have our interests at heart, or at best, are not connected enough to us to know what we really want. Taking ownership of something – however small – plants the seeds of empowerment that (when the time is ripe) can grow to astonishing heights.

Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall of River Cottage captures this beautifully in his book River Cottage Everyday:

I find this flourishing of domestic poultry-keeping enormously encouraging. On the simplest level, it signifies that lots of people are producing a little more of their own food. And once you have a few chickens, you find yourself, almost without trying, living in a slightly more sustainable way: you give your kitchen scraps to the birds, they provide you with eggs of course, but also manure, which is great on the compost heap, and if you’ve got a compost heap, you’re a step closer to growing even more of your own lovely fruit and vegetables … But everyone who keeps even the smallest of chicken flocks is also dealing a blow to factory farming – every egg that comes from a garden hen is one less that’s come from a caged, suffering one. Likewise, every home-grown chicken roasted for Sunday lunch is one less intensively reared, supermarket bird sold.

The beginnings of self-sufficiency builds confidence too. Starting your own venture might not seem so far off, if you can break it down into a process of learning and application. This translates to larger organisations too. People who are used to doing in their own lives, tend to be more nimble and not afraid to get things done in the workplace. This characteristic even has a term — “intrapreneur” — someone not paralysed by red tape or what they view as the boundaries of their role, but willing to work within the rigid structures of a large organisation to bring about greater change.

Making as a skill for survival

So we start small, then we build. We might begin to trust in our own abilities and experience incremental effects, like the ones described by Fearnley-Whittingstall, and one day we might find this newfound doing-ness has increased our chances of survival.

Sound extreme?

Well, there’s a lot going on the in the world today. Climate change is an undeniable issue, yet Australia’s leaders continue to deny it. This means that extreme weather, drought and food crises are all very real issues we will face in our future. There’s a lot we can do to create resilient communities, but that means thinking ahead and up-skilling before it’s needed.

Says Milkwood Permaculture co-founder Kirsten Bradley:

“Ok so society fails and your community has to fend for itself. If you hear that the much-needed doctor, or the midwife, or the blacksmith in your community is in danger, everyone’s going to come running, because they’re defending an essential community resource, not just an individual.

So rather than building a fortress and getting lots of guns and probably dying of loneliness, how about becoming so bloody useful that your immediate community can’t do without you? Sounds safer to me. More fun, too.”

So while our politicians get caught up in blame and games, let’s just get on with life. There’s no need to wait for permission or the big idea — we have all we need to get started. Start small, start now.